Authored by Dr. Susan E. Brown, PhD

If you’re here because you’ve recently been diagnosed with osteoporosis, the first thing I want you to do is take some deep breaths. Osteoporosis is serious, but you’re not helpless. Despite your concerns about weak bones, there’s plenty you can do to improve the strength of your bones.

Whether you’ve had signs and symptoms of osteoporosis or no bone loss symptoms at all until you had a bone scan, you’ve just gotten a wakeup call. Something unhealthy has been developing for a while in your body, and it’s time for you to take action. To do that, however, you’ll need to learn some things about the definition of osteoporosis — what it is, and just as important, what it isn’t.

There’s a lot of misinformation and misunderstanding about bone loss and women’s bones. Some of it may not really apply to your situation. But I’ll help you learn what is the best and safest treatment for osteoporosis and figure out what will work for you to naturally improve your health and avoid (or heal from) a fracture. You should know up front that you’re going to get conflicting advice over time, and there is a lot of controversy on osteoporosis treatment. Bookmark this page now so you can come back to it. It’s a short guide for you, and it may be helpful to share it with your family and friends who need to understand what’s happening to you.

Table of contents

What are the risk factors for osteoporosis and low bone density?

Conventional treatments for osteoporosis

The natural approach to osteoporosis and bone health

What is osteoporosis?

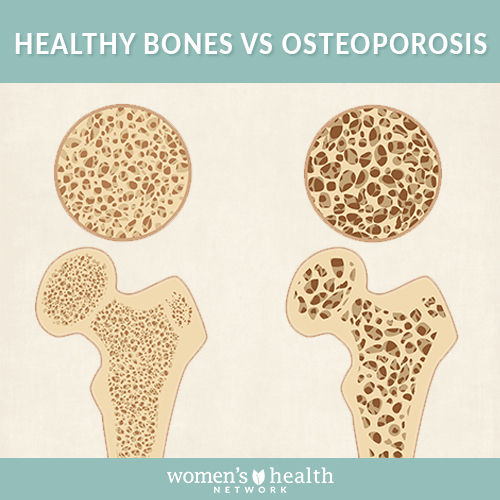

The literal meaning of the word “osteoporosis” is “porous bones.” The disease got that name because people who have osteoporosis often have big gaps and openings in the bone’s structure that weaken the bone and make it prone to fractures. And fractures are the most concerning aspect of osteoporosis, particularly in older women. But where so many people talk about osteoporosis in terms of bone thinning, the true concern is more about bone weakness. And the two aren’t automatically the same thing. A spider’s web is delicate, but it’s extremely strong — and in the same way, thin bones aren’t necessarily weak ones.

It’s also true that dense bones are not necessarily strong bones. A significant number of women who have osteoporotic fractures that identify their bones as weakened have what’s considered “normal” bone density. So it’s important to understand that bone density is just one of a number of factors that help identify whether your bones are strong or fragile, and possibly not even the most important one. Other key factors in osteoporosis need consideration. For example, if your bones are thin, how did they get that way? Were they always that way, and you just didn’t know, or have you lost a lot of bone recently?

And if you did, are you still losing bone? And if so, why? The why? question is probably the most important one. It’s unusual that osteoporosis “just happens.” There’s often something else going on underneath, whether it’s the hormonal changes of menopause or something a lot more complicated. In essence, osteoporosis often isn’t so much a stand-alone disease as a sign that there’s something going on that needs your attention — a symptom of a bigger, or maybe just less obvious, problem.

What are the risk factors for osteoporosis and low bone density?

There are many different risk factors that can contribute to bone loss. Some are hereditary, some are age related, some are lifestyle related and some stem from underlying chronic diseases, like diabetes or other inflammatory disorders. Let’s look at them one at a time.

Genetics

There’s no question: If near relatives in your family tree have had osteoporosis, or have had a major fracture after an otherwise minor fall (low-impact fracture is one of the key hallmarks of osteoporosis), then it’s likely that you have a greater risk of developing osteoporosis yourself. But genes aren’t destiny, and in many cases the genetic risk manifests only when certain lifestyle factors — diet, exercise, smoking, stress — are included in the mix. So if you know this hereditary risk exists, it gives you the opportunity to do something about those other factors.

Life stage and hormonal imbalance

Osteoporosis is considered a “disease of aging.” That makes it sound as though bone weakness is inevitable, and it’s not. What is inevitable, at least for women, is the menopause transition — sooner or later, we all go through it. The hormonal shifts of menopause, particularly the loss of estrogen, are associated with decreased bone mass in most women. This is only a major issue if, as mentioned earlier, your bones become weakened as well as thin. That happens most often if you didn’t build adequate bone mass during your youth, such as women who had poor nutrition or eating disorders in adolescence and young adulthood. It can also happen if you have other factors that affect your bone health while you’re going through menopause — particularly a decrease in exercise (more on that later).

Body type

Thin, small-boned women start out with less bone mass than larger women, so they have less to lose. This doesn’t necessarily mean they’re at risk of fracture, though, if they get plenty of exercise and balanced nutrition. But it does mean that when other factors come into play (such as a chronic illness or a dietary or hormonal imbalance), a thin, small-framed woman is at greater risk than a larger one would be.

Lifestyle factors

Diet and nutrition

You probably have already heard a lot about calcium and its importance for bone health. But what you’ve heard is at best incomplete and at worst, seriously exaggerated, often by people who want to sell you more cow’s milk. Do your bones need calcium? Well, yes — it’s one of the major minerals present in the bones’ structure.

But it’s by no means the only thing we need to keep bones strong. You can drink milk by the gallon, but if you aren’t getting other key nutrients, such as magnesium, Vitamin D, potassium and a host of others, all that calcium won’t do your bones any good. In fact, it could do the rest of your body (especially the cardiovascular system) more harm than good. This means that one way you can address your risk of osteoporosis and the potential fractures that come with it is to learn about good nutrition and how to get the full suite of nutrients for long-term bone health from a healthy diet. Then you can make an educated decision about how to use high quality nutritional supplements to make up for dietary deficiencies.

Exercise

We’ve all heard how important exercise is for health. But exercise is even more crucial for bone health because it has a direct effect on how bone renews itself. Every time your foot hits the ground or your muscles flex, your bones are signaled to strengthen. The harder the impact and more frequent the “load” on your muscles, the “louder” the signal to bones. Your bones know the difference between a casual stroll and power walking, and between power walking and jumping rope. And they respond to those different impacts accordingly.

Similar signals are generated by the tug of your muscles on the bones, even in low-impact exercises like yoga, tai chi or swimming. So if running is not your favorite thing to do, you can still get results from low-impact exercises. Resistance (weight-bearing) exercises are just as important as high-impact cardio, if not more so, to strengthening bone. Just be sure to learn how to do them correctly so you don’t injure yourself. Following an exercise program just for bone health is a good idea. But if you’re hesitant to take up exercise because you don’t think you’re strong enough to do it, don’t stress. Studies have shown that any exercise is better for your bones than none, as long as you do it regularly.

Smoking

Smoking is bad for more than just your lungs. It’s an overall physiologic source of stress. If you smoke, quit. We know you’ve heard that before, and we also know it’s a lot easier said than done. But it really is that important. It’s probably the single most important step you can take to improve not just your bone health, but your total health.

Stress

And while we’re talking about stress — strange as it might seem, it too is a risk factor for osteoporosis. Stress (the chronic kind) produces physiologic responses that are harmful to bone over the long run. The hormone cortisol, released from the adrenal glands in response to stress, causes bone-building osteoblasts to be shorter in lifespan and less effective in function.

Chronic illness

Certain chronic illnesses can lead to bone loss and osteoporosis as well. Diabetes, inflammatory bowel disorders or certain autoimmune disorders such as Graves’ disease (hyperthyroidism) are examples. Medications such as corticosteroids and the antiseizure medication phenytoin, as well as some cancer drugs, cause bone loss as well. Even proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) used for acid indigestion can lead to bone weakening.

Diagnosing osteoporosis

For some women, the diagnosis of osteoporosis comes after an unexpected fracture. We’re not talking about the kind of break that comes from falling off a 10-foot ladder onto a concrete driveway. We’re talking about breaking a bone in your foot after tripping over a rug, or maybe fracturing a wrist just by accidentally bumping into a door frame. Or even going to your doctor because you have back pain and discovering you have a vertebral fracture. All of these fractures happen when bones that are subjected to normal, mundane loads can’t support them.

A question that arises when it comes to assessing bone health is: Do you have the right doctor? It’s an unfortunate fact of life in modern America that healthcare providers are under pressure to push patients through their offices in the least amount of time possible. This similarly puts them under pressure to “solve” a health problem via prescription medications. The “magic bullet” drug approach doesn’t necessarily work well when it comes to bone health. And bone drugs don’t come without side effects. Halting and reversing bone loss is not a short-term proposition. If you’re working with a provider who wants to treat it that way, you may want to reconsider the relationship.

Remember, you didn’t lose all that bone overnight, and quick fixes to long-term problems don’t tend to work well. You’ll do better with a provider who understands that. So let’s look at what you need to do to take care of your bones.

The stages of osteoporosis

From birth through young adulthood — around age 30 — our bodies are generally in a bone-building mode. The osteoblast cells that add bone tend to be much more active and abundant in this stage of life. In a nutshell, as long as we get adequate nutrition and exercise and have no out-of-the-ordinary physical or emotional stresses on the body, we should be building a lot more bone than breaks down year after year. But once we get to middle adulthood that changes, and our bones start to change in stages:

Stage 1

Starting in your early 30s, bone building drops off and bone breakdown starts to increase to where the two processes are equal. Your bone density stops increasing, but all else being equal, you probably have little to worry about with respect to fractures.

Stage 2

Usually starting around age 35, bone breakdown starts to outpace bone building, and bones begin to thin. Even so, bones generally remain strong enough to resist fracturing, unless there’s a really serious issue (such as chronic illness or serious malnutrition) affecting them.

Stage 3

Most women start to experience menopause symptoms around age 45 to 55. At the same time, some women start to develop excessive bone thinning and weakness. This is in part because of the reduction in estrogen and the stresses that the menopause transition can produce — insomnia, emotional disturbances and fatigue among them. This phase of higher bone loss and greater fracture risk is often when women are first encouraged to have a bone density assessment. (It’s also when many women are told they have osteopenia, which is mistakenly labeled as “early osteoporosis.”) There aren’t many obvious bone loss symptoms. A few that might signal a cause for concern include receding gumline and loss of teeth, brittle or weak fingernails, decreased grip strength or overall loss of muscle strength, or poor balance.

Stage 4

In this active osteoporosis phase, weakness in bones starts to manifest in physical symptoms. Pain in the bones or joints, reductions in height (from fractures in vertebrae) and low-impact fractures are some signs of osteoporosis.

Can osteoporosis be cured?

With multiple factors contributing to bone loss and osteoporosis, it’s hard to talk about “curing” osteoporosis. Some of these factors, you can’t change. But many other factors you absolutely can. So your best approach to reducing your risk of osteoporotic fractures is to take steps to reduce or eliminate the factors you’re able to change — allowing your body to recover some of what it has lost. And, more important, taking these steps won’t just affect your bones — it will benefit your overall health as well.

Conventional treatment of osteoporosis

If you have any of the symptoms signaling that you might have stage 3 or 4 osteoporosis, or other serious risk factors for osteoporosis or fractures, your healthcare provider might well refer you for a DEXA test and initiate treatment. And as we mentioned above, the standard operating procedure in most medical practices is to prescribe medications even though, ironically, osteoporosis treatment guidelines start in the same place we do, by recommending that physicians begin with encouraging patients to maximize their nutrition (the focus is mostly on Vitamin D and calcium, but some experts have begun acknowledging that a more comprehensive look at nutrient intake may be necessary).

Drugs and side effects

The go-to drugs for osteoporosis are bisphosphonates, but these drugs aren’t without controversy. Aside from problematic side effects such as gastrointestinal upset, muscle pain, hypocalcemia and inflammation of the eyes (uveitis), the drugs are associated with rare but serious health concerns when used long term. These include osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ); sudden, unusual fractures called atypical fractures of the femur (AFF); abnormal heartbeats and atrial fibrillation (AF); and esophageal cancer. Other bone-building drugs have become available in recent decades, but they all have concerns. Drugs such as denosumab (Prolia) and teriparatide (Forteo) have side effects like fever, nausea, dizziness, muscle cramps, headache and gastrointestinal disturbances.

These drugs are analogs of specific biochemicals that promote bone building, but their effects tend to be short-lived. Each drug may be prescribed for no more than a year or two before the patient is switched to a bisphosphonate. It’s ironic to us that conventional healthcare approaches to osteoporosis are so quick to gloss over the nutritional and exercise components that guidelines emphasize, and a mountain of research supports, as an effective starting point for restoring bone health. If healthcare providers weren’t so quick to prescribe medications — and patients so accustomed to accepting them — both might find that a more natural approach to bone health can be extremely effective, if only you give it time to work.

The natural approach to osteoporosis and bone health

The natural approach to bone health is based on understanding what the body needs to build bone. Exercise is one underpinning; optimizing nutrient intake, including taking a nutritional supplement for bone health, is another. At the same time, you want to reduce exposure to factors that negatively impact bones — especially foods high in sugar and chemical additives, but also emotional stress. When all of these steps are undertaken together, it can help the body to slow bone turnover and even rebuild some of the lost bone.

Exercise

Let’s start by busting a myth. You do not need to lift weights two hours a day, six days a week to build bone. Yes, muscle and bone are built together. But that doesn’t mean you have to become Ms. Universe. Any exercise is good exercise. Resistance exercise is going to be somewhat better because the load it puts on your bones signals the need for bone building to occur. But if you’re not physically ready for that, you can make a good start simply by walking, swimming or doing other low-impact exercise that moves your entire body. Studies show that even a little bit of exercise is good for bone. And you’re more likely to do it if you enjoy it. So the first tip is, get moving and do something that’s enjoyable enough that you’ll keep doing it.

Dietary changes

Calcium and Vitamin D, as we mentioned earlier, are two nutrients that just about everyone recommends for better bone health. But let’s face it, bones aren’t made of milk and sunshine. There’s ample evidence that these two nutrients alone just aren’t enough (and in fact, too much calcium can actually be counterproductive). For example, Vitamin K, which is found in leafy green vegetables, and magnesium, found in nuts and legumes, have been shown to have particular benefit for bones. Other vitamins and minerals that play key roles in bone maintenance include boron, silicon, Vitamin C, zinc, manganese, potassium and phosphorus.

For many Americans, the full suite of nutrients needed to support healthy bones isn’t available in the diet — because too many Americans lack a nutritionally sound eating pattern. The standard American diet tends to be high in animal fats and carbohydrates (flour, sugar and starch) and low in the plant-based foods that provide the majority of micronutrients. As a “workaround” strategy, it’s possible to use supplements to boost your intake of these nutrients. And as long as you select high-quality products, this is a good way to jump-start your bone health journey. But the ideal way to improve your nutrient status is through foods. This is for more reasons than just making sure you get “enough” Vitamin K or magnesium. Eating a balanced, plant-based diet also offers you a variety of compounds that can reduce one of the important physical stresses affecting bones: acid.

Alkaline diet for osteoporosis

Anything you eat gets broken down into base chemicals. Some of these chemicals, if you remember your high school science, are acidic and others are alkaline. You might guess intuitively that nutrient-rich vegetables are the source of alkaline compounds in the body. Whereas sugar, starches and fatty meats — all the components of the cheeseburger-soda-and-fries meal — produce acidifying compounds. Those compounds tilt the blood away from the slightly alkaline range of 7.35–7.45 that is essential for health. The body compensates by releasing minerals such as calcium and potassium from the bones. Thus, an acid-forming diet produces pressure on the bones to break down rather than build. The solution is to get away from the foods that are acid forming and emphasize the ones that are alkaline — fruits and vegetables, whole grains, and legumes. Limited amounts of lean meat are OK too. Keep breads, sugars and processed foods to a minimum.

Minimize your stress

Chronic stress takes a huge toll on our health — it increases the body’s acid load (and keep in mind, this can be physical stress — as occurs during the menopause transition — as well as emotional or mental stress). Also keep in mind, it’s not just the day-to-day stress of modern life, but also issues from the past which can manifest themselves in new places in our lives. Cortisol, our major stress hormone, can be extremely detrimental to bone and other organs if it remains at high levels around-the-clock. Be good to yourself and seek help if you need it or simply give yourself more breaks — whether it’s to take a relaxing bath or simply reading alone on the couch for an hour. Anytime you quiet your mind and relax your body, you can lower your stress level.

You have choices about your bone health

I’m not alone in thinking the natural approach I described makes sense — the Surgeon General of the United States issued treatment guidelines in 2004 that stated the first two steps a physician should recommend to any patient with osteoporosis, osteopenia or fragility fracture are improvements to dietary and exercise habits, followed by investigation of potential causes of bone loss.

This is where you can take control! You can look at osteoporosis and bone weakening in relationship to your whole body and your whole lifestyle, instead of viewing it as a bone disorder which seems to happen for no good reason as you age. With the new perspective you can then see that there are many natural ways to restore and maintain bone health no matter what your age — from 12 to 102.

Start your own bone health journey

So, where do you want to start in your journey of building bone strength? Which burdens can you modify? There are some things you cannot change, but there are others that you can — so start there. A simple start might be to make a new exercise commitment, to set the goal of eating 3 to 4 cups of vegetables a day, or to begin meditating and reducing emotional stress.

All of the bone-building — and bone-depleting — factors are interrelated, and even small changes over time add up and can make a big difference! And it’s not unusual to find that changing one factor in a small way can also improve one of those other factors that you can’t change directly — for instance, changing your diet or reducing your stress burden may not only help your bones, but also improve digestive or autoimmune disorders, giving you a doubly beneficial effect. I encourage you to work with a supportive health care professional who can help you to monitor and track your progress.

Finally, one last thought on the use of bone medications. If you and your doctor have decided that you are one of those individuals at high fracture risk who really needs to use bone drugs, please keep in mind that the success of your drug-centered bone program will be greatly enhanced if you combine medication use with an approach that focuses on comprehensive bone-building nutrition and lifestyle. In other words, taking these all-natural steps is just as important if you end up deciding to take a drug.

Your diagnosis is an opportunity

If it sounds like I’m urging you to “look on the bright side” of a finding most people would dread, well, I am — positive thinking is a good way to support your bones, after all — but there’s more to it than that! The most important benefit of getting an osteoporosis diagnosis is the opportunity it gives you to improve your bone health, as well as your overall health. Being told you have osteoporosis is a wake-up call and reminds you to take care of yourself — which is especially important if you’ve spent much of your life taking care of others.

There are many options available to address the problem once you understand it exists. Why not start with checking in on the health of your bones? You can use our free Bone Health Quiz to get an overview of your risk factors and customized recommendations for your first steps towards stronger bones.

Frassetto, L., et al. 2000. Worldwide incidence of hip fracture in elderly women: Relation to consumption of animal and vegetable foods. J. Geront.: A. Med. Sci., 55A (10), M585–M592. URL (abstract): https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11034231 (accessed 10.14.2008).

Mazess, R. 1987. Personal communication, Continuing Education Course on Osteoporosis: Harvard University.

Fujita, T., & Fukase, M. 1992. Comparison of osteoporosis and calcium intake between Japan and the United States. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med., 200 (2), 149-152. URL (abstract): https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1579574 (accessed 10.14.2008).

Garn, S. 1967. Nutrition and bone loss: Introductory remarks. Fed. Proc., Nov/Dec, 1716.

Wainwright, S., et al. 2005. Hip fracture in women without osteoporosis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab., 90 (5), 2787-2793. URL: https://jcem.endojournals.org/cgi/content/full/90/5/2787 (accessed 10.14.2008).

International Osteoporosis Foundation. 2008. FRAX – WHO Fracture Risk Assessment Tool. URL: https://www.iofbonehealth.org/health-professionals/health-economics/frax.html (accessed 6/13/08).

Carmona, R. 2004. Bone health and osteoporosis: A report of the Surgeon General (Preface). US Department of Health and Human Services, Rockville, MD. URL: https://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/bone-health/ (accessed 10.14.2008).

Robbins, J., et al. 2007. Factors associated with 5-year risk of hip fracture in postmenopausal women. JAMA, 298 (20), 2389-2398. URL: https://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/298/20/2389 (accessed 10.14.2008).

Brown, S. 2008. How can we tell who will fracture? URL: https://www.betterbones.com/bonefracture/whowillfracture/ (accessed 01.16.2009).

National Institutes of Health. 2007. Fact sheet. Osteoporosis. URL (PDF): https://www.nih.gov/about/researchresultsforthepublic/Osteoporosis.pdf (accessed 10.12.2009).