Authored by Dr. Sarika Arora, MD

Molly had been lactose-intolerant for many years before having children. Surprisingly, she went through two pregnancies completely able to digest dairy foods, and thought she’d overcome whatever the problem was — until faced with a newborn who had nursing difficulties, a 2-year-old and a full-time job. Suddenly it seemed like everything she ate gave her bloating, gas and then eventual diarrhea. She was tired, irritable, unable to exercise — as well as running frequently to the bathroom. As she relayed her story, it sounded a lot like leaky gut.

Molly had leaky gut syndrome, a digestive disorder that is not yet fully understood, especially in conventional medicine. But clearing it up is a top priority if you want to maintain your health. As it turned out, Molly’s leaky gut caused foods that ordinarily were fine for her to wreak havoc on her system. With a little extra help Molly was able to heal her gut and then come back to enjoying nearly all her favorite foods — without the embarrassing symptoms!

Most people do not understand that digestion is absolutely the foundation of our health. Because of the way our bodies are connected, inflammation in the gut can eventually lead to inflammation in the bones, heart, brain or beyond, making osteoporosis, heart disease, Alzheimer’s or other diseases you may have a genetic predisposition for more likely as you age.

Let’s take a look at what is leaky gut syndrome, and then how you can resolve it naturally.

Is there a test for leaky gut?

Yes, there is a test for leaky gut, but testing may not even be necessary. Most women suffering from what’s probably leaky gut note marked improvement within 2 weeks of initiating our Women’s Health Network protocol.

If you are interested in being tested, ask your practitioner for an intestinal permeability test, also known as the lactulose–mannitol challenge. This test measures how quickly the sugars lactulose and mannitol cross the lining of the gut.

What is leaky gut?v

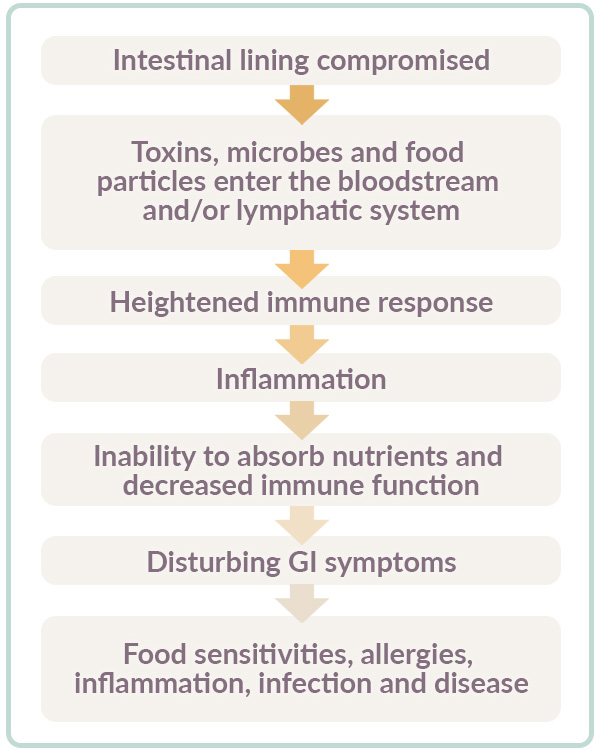

Along the lining of healthy intestines, cells are sealed together by what are known as tight junctions. These junctions are the gatekeepers that allow or bar particles from the gut’s interior to move into the body’s circulatory system. When your intestinal lining is compromised, particles can “leak” inappropriately through these cells and their junctions, and pass into the bloodstream or lymphatic system. These particles may include things such as incompletely digested chunks of food, or microbes, or wastes, toxins, and even antigens and pathogens.

The leaking of these particles alerts your body that something is wrong, then your immune system tries to come to the rescue by igniting inflammation. As inflammation increases, the layer of beneficial bacterial colonies lining the intestines then decreases, which only makes the problem worse.

There are two major concerns with leaky gut. Firstly is the inability for women to digest and absorb food and nutrients properly. Secondly is a compromised immune system, which is the source of most of the symptoms women feel with leaky gut. Your gut plays a crucial role in immune function because it contains special areas called gut-associated lymphatic tissue (GALT) that protect you from allergy-causing food antigens and disease-carrying microbes. With leaky gut, these and other harmful substances can gain access to your blood stream then travel far and wide throughout the body.

Causes of leaky gut

The precise cause for a woman’s leaky gut can be difficult to nail down because there are so many potential triggers. Here are some — but not all — of the contributing factors.

- Genetic predisposition to heightened immune response

- Consuming foods to which you are sensitive or allergic

- Overindulging in refined and overprocessed foods

- Exposure to heavy metals, radiation, certain drugs, toxins and other noxious agents

- Excessive alcohol and/or caffeine intake

- Suboptimal production of digestive enzymes

- Imbalanced gut flora (dysbiosis)v

So many women have a digestive imbalance. There are potential preexisting conditions and also events commonly associated with leaky gut. Upon reflection, most women can pinpoint the time wvhen they first noticed a change in their digestion. With Molly, this was soon after the birth of her baby girl.

In reality, anything that damages the mucosal lining of the GI tract can contribute to leaky gut. Molly’s problem likely originated with a lactose intolerance that had quietly simmered away for years, but which came to a rolling boil in response to her growing responsibilities.

It bears mention that certain medications, treatments and conditions can damage the lining of your gut. Antibiotics are one of the biggest offenders, because they annihilate your friendly gut flora. Radiation, chemotherapy, steroid drugs (corticosteroids), aspirin, ibuprofen, naproxen, other NSAID’s and especially antibiotics can all increase intestinal permeability. Leaky gut may also show up along with parasites, Crohn’s disease, celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome that is traced to food intolerance.

It’s often said that the gut is the key to overall health, and this statement becomes very clear with leaky gut. Not only can leaky gut lead to food sensitivities and allergies, explained below, but an abundance of toxins in the system can burden the liver and also lead to chronic inflammation. Inflammation has the potential to be linked to a whole host of disorders, such as chronic fatigue syndrome, heart failure, depression, multiple sclerosis, lupus, vasculitis, rheumatoid arthritis, asthma, osteoporosis and more.

Here’s the scoop on leaky gut and food allergies

When you have leaky gut syndrome, your body is caught in a self-perpetuating, semi-infectious, inflammatory state. If your immune system is continually being stimulated by specific food antigens that are leaking into circulation, and you continue to consume those foods, then you could easily develop an allergic response or sensitivity to those foods. Your immune system remembers those foods as triggers, so calls up the same inflammatory reaction at each re-encounter. This is what happened for Molly with dairy, and, when the intestinal lining failed to heal, yeast and eggs became a problem as well.

Here’s the general course leaky gut takes in the pathway to disease.

Buckwheat for your belly

If you’re looking for a simple, yet healthy breakfast that is easy to digest, experiment with cream of buckwheat (also known as buckwheat grits). Depending on your taste, you can cook these into a sweet or savory breakfast in no time!

Sweet Cream of Buckwheat

- Cut one pear or apple into thin slices

- Saute fruit slices in coconut oil until soft and turning brown

- Sprinkle with cinnamon and nutmeg

- Add ¼ cup of buckwheat grits and be sure to cover them in oil and fruit juice before adding water

- Add 1 ¼ cups of water

- Cook covered until grits are soft (about 20 minutes) and top with walnuts or almonds

- Optional: add 1 tbsp Greek yogurt plus a teaspoon of stevia or honey

Savory Cream of Buckwheat

- Saute 1 garlic bulb (chopped), ½ medium sized onion (sliced thinly) and a cup of chopped mushrooms until mushrooms have released their juices and the onions are soft

- Add ¼ cup of buckwheat grits and mix in with vegetables and oil

- Add 1 ¼ cups of water and cook grits until soft (about 20 minutes)

- Stir in a handful of baby spinach until wilted

- Top with ¼ cup of chopped almonds

- Top with blueberries for added antioxidants

- Add salt and pepper to taste

References and further reading

DeMeo, M., et al. 2002. Intestinal permeation and gastrointestinal disease. J. Clin. Gastroenterol., 34 (4), 385–396. URL (abstract): https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11907349 (accessed 11.24.2009).

Krantz, B., et al. 2005. A phenylalanine clamp catalyzes protein translocation through the anthrax toxin pore. Science, 309 (5735), 777–781. URL: https://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/309/5735/777 (accessed 11.24.2009).

Nejdfors, P., et al. 2000. Mucosal in vitro permeability in the intestinal tract of the pig, the rat, and man: Species-and region-related differences. Scand. J. Gastroenterol., 35 (5), 501–507. URL (abstract): https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10868453 (accessed 11.24.2009).

Thomson, A., et al. 1997. Small bowel review — Part II. Can. J. Gastroenterol., 11, 159–165. URL (PDF): https://www.pulsus.com/journals/abstract.jsp?sCurrPg=journal&jnlKy=2&atlKy=2375&isuKy=173&isArt=t

Gardner, M. 1988. Gastrointestinal absorption of intact proteins. Ann. Rev. Nutr., 8, 329–350. URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3060169 (accessed 12.18.2009).

Liska, D., & Bland, J. 2005. Chapter 17. Digestion and excretion. In Textbook of Functional Medicine, ed. D. Jones & S. Quinn, 192. Gig Harbor, WA: Institute for Functional Medicine.

Wikipedia. 2009. Tight junction. URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tight_junction (accessed 11.24.2009).

Liska, D., & Bland, J. 2005. Chapter 17. Digestion and excretion. In Textbook of Functional Medicine, ed. D. Jones & S. Quinn, 193. Gig Harbor, WA: Institute for Functional Medicine. Sult, T. Chapter 24. Clinical approaches to gastrointestinal imbalance.

Brandtzaeg, P. 2007. Why we develop food allergies. Am. Sci. URL: https://erweb2.eresources.com/issues/id.1012,y.0,no.,content.true,page.1,css.print/issue/ (accessed 09.09.2009).

Sult, T. 2005. Chapter 24. Digestive, absorptive, and microbiological imbalances. In Textbook of Functional Medicine, ed. D. Jones & S. Quinn, 330. Gig Harbor, WA: Institute for Functional Medicine.

Galland, L. 2007. Foundation for Integrated Medicine. Leaky gut syndromes: Breaking the vicious cycle. URL: https://mdheal.org/leakygut.htm (accessed 11.24.2009).

Farhadi, A., et al. 2008. Susceptibility to gut leakiness: A possible mechanism for endotoxaemia in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Liver Int., 28 (7), 1026–1033. URL (abstract): https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18397235 (accessed 12.18.2009.)

McGonagle, D., et al. 1998. Classification of inflammatory arthritis by enthesitis. Lancet, 352 (9134), 1137–1140. URL (abstract): https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-673(97)12004-9/abstract (accessed 11.24.2009).

Darlington, L., & Ramsey, N. 1993. Review of dietary therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. Br. J. Rheumatol., 32 (6), 507–514. URL: https://rheumatology.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/abstract/32/6/507 (accessed 12.18.2009).

Rooney, P., et al. 1990. A short review of the relationship between intestinal permeability and inflammatory joint disease. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol., 8 (1), 75–83. URL (abstract): https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2189626 (accessed 11.25.2009).

Keshavarzian, A., et al. 2009. Evidence that chronic alcohol exposure promotes intestinal oxidative stress, intestinal hyperpermeability and endotoxemia prior to development of alcoholic steatohepatitis in rats. J. Hepatol., 50 (3), 538–547. URL (abstract): https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19155080 (accessed 11.24.2009).

Sult, T. 2005. Chapter 24. Clinical approaches to gastrointestinal imbalance. In Textbook of Functional Medicine, ed. D. Jones & S. Quinn, 440. Gig Harbor, WA: Institute for Functional Medicine.

Douek, D. 2007. HIV disease progression: Immune activation, microbes, and a leaky gut. Top HIV Med., 15 (4), 114–117. URL (abstract): https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17720995 (accessed 11.24.2009).

Weil, A. 2005. What is leaky gut? URL: https://www.drweil.com/drw/u/QAA361058/what-is-leaky-gut.html (accessed 11.25.2009).

Wikipedia. 2009. Leaky gut syndrome. URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leaky_gut_syndrome (accessed 11.24.2009).

Hollander, D. 1999. Intestinal permeability, leaky gut, and intestinal disorders. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep., 1 (5), 410–416. URL: (abstract): https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10980980 (accessed 11.24.2009).

Maes, M., & Leunis, J. 2008. Normalization of leaky gut in chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) is accompanied by a clinical improvement: Effects of age, duration of illness and the translocation of LPS from gram-negative bacteria. Neuro. Endocrinol. Lett., 29 (6), 902–910. URL (abstract): https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19112401 (accessed 11.24.2009).

Wikipedia. 2009. Leaky gut syndrome. URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leaky_gut_syndrome (accessed 11.24.2009).

Maes, M. 2008. The cytokine hypothesis of depression: Inflammation, oxidative & nitrosative stress (IO&NS) and leaky gut as new targets for adjunctive treatments in depression. Neuro. Endocrinol. Lett., 29 (3), 287–291. URL (abstract): https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18580840 (accessed 11.24.2009).

[No author listed.] Leaky gut syndrome. (LGS) — intestinal permeability. The Environmental Illness Resource. URL: https://www.ei-resource.org/illness-information/environmental-illnesses/leaky-gut-syndrome-(lgs) (accessed 11.24.2009).

Wikipedia. 2009. Leaky gut syndrome. URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leaky_gut_syndrome (accessed 11.24.2009).

Sult, T. 2005. Chapter 24. Digestive, absorptive, and microbiological imbalances. In Textbook of Functional Medicine, ed. D. Jones & S. Quinn, 334. Gig Harbor, WA: Institute for Functional Medicine.

Rooney, P., et al. 1990. A short review of the relationship between intestinal permeability and inflammatory joint disease. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol., 8 (1), 75–83. URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2189626 (accessed 12.18.2009).

Wikipedia. 2009. Leaky gut syndrome. URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leaky_gut_syndrome (accessed 11.24.2009).

Reference on symptoms of leaky gut syndromes

Galland, L. 2007. Foundation for Integrated Medicine. Leaky gut syndromes: Breaking the vicious cycle. URL: https://mdheal.org/leakygut.htm (accessed 11.24.2009).

Reference on testing for leaky gut

Hyman, M. 2006. Lab tests. URL: https://www.drhyman.com/LabTests-Inflammation/#Lactulose (accessed 12.18.2009).

Reference on medical treatments that increase intestinal permeability

Sult, T. 2005. Chapter 24. Clinical approaches to gastrointestinal imbalance. In Textbook of Functional Medicine, ed. D. Jones & S. Quinn, 440. Gig Harbor, WA: Institute for Functional Medicine.

References for targeted natural solutions for leaky gut

van der Hulst, R., et al. 1993. Glutamine and the preservation of gut integrity. Lancet, 341 (8857), 1363-1365. URL (abstract): https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8098788 (accessed 12.18.2009).

Klimberg, V., et al. 1990. Oral glutamine accelerates healing of the small intestine and improves outcome after whole abdominal radiation. Arch. Surg., 125 (8), 1040–1045. URL: (abstract): https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2378557 (accessed 12.18.2009).

Souba, W. 1991. Glutamine: A key substrate for the splanchnic bed. Annu. Rev. Nutr., 11, 285-308. URL: https://arjournals.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev.nu.11.070191.001441 (accessed 12.18.2009).

Souba, W. 1989. The gut — a key metabolic organ following surgical stress: Benefits of glutamine supplementation. Contemp. Surg., 35 (5A), 5–13.

Sult, T. 2005. Chapter 24. Clinical approaches to gastrointestinal imbalance. In Textbook of Functional Medicine, ed. D. Jones & S. Quinn, 440. Gig Harbor, WA: Institute for Functional Medicine.

Robinson, R., et al. 2001. Nutritional benefits of larch arabinogalactan. In Advanced Dietary Fibre Technology, ed. B. McCleary & L. Proskey, 445–446. Oxford: Blackwell Science, Ltd.

Deters, A., et al. 2005. Kiwi fruit (Actinidia chinensis L.) polysaccharides exert stimulating effects on cell proliferation via enhanced growth factor receptors, energy production, and collagen synthesis of human keratinocytes, fibroblasts, and skin equivalents. J. Cell Physiol., 202 (3), 717–722. URL (abstract): https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15389574 (accessed 12.18.2009).

Sturniolo, G., et al. 2001. Zinc supplementation tightens “leaky gut” in Crohn’s disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis., 7 (2), 94–98. URL (abstract): https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11383597 (accessed 11.25.2009).