Authored by Dr. Mary James, ND

For women with insomnia, being awake when the rest of the world is asleep is pure misery and frustration. Sleep is part of your basic biological rhythm — a process that will naturally reset itself when you address any underlying physical and psychological issues that need attention.

Chronic insomnia also has its own set of unpleasant physical symptoms and is a genuine concern for many women. Sleeplessness has serious effects on your health because it:

- disturbs metabolism

- disrupts cognitive and neurotransmitter function

- undermines immunity

- imbalances adrenal function

- upsets overall hormonal balance

Conventional practitioners often turn to sleep medications, like Ambien, to treat insomnia. But a better first step is to look for clues that can uncover the root source of your insomnia. Then you can restore healthy sleeping patterns naturally and permanently.

Your natural sleep-wake cycle — the circadian rhythm

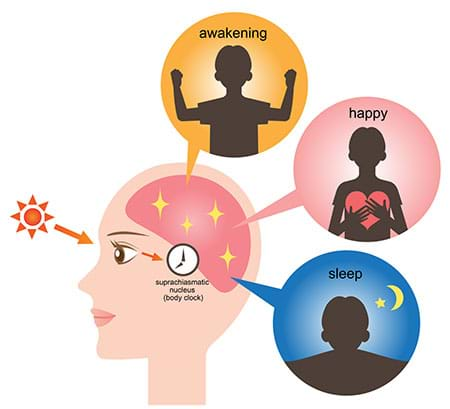

Your circadian rhythm is a 24-hour cycle linked to the rising and setting of the sun. Deep in your brain, a tiny, powerful cluster of nerve cells called the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) works 24/7 as an internal clock. It programs key activities like cell regeneration, detoxification, brain activity patterns, and production of hormones that regulate during the sleep-wake cycle.

When it gets dark, your SCN begins to lower body temperature and sends signals to release melatonin, the hormone that makes you sleepy. But at night, exposure to light— both natural and artificial — counters that natural slow-down process by raising body temperature, tamping down melatonin and releasing “wake-up” hormones like cortisol. Your internal pathways are so sensitive to light and darkness that it’s easy for them to be thrown off. Even switching on the light for a few seconds can shift your circadian cycle by more than 40 minutes.

Fortunately, your circadian rhythm can reset itself — but only up to a point. When you have a newborn baby, work the night shift, or travel across time zones, your inner clock will be able to adjust to the change temporarily. While this allows you to function, it is not a long-term solution (think jet lag).

For most sleepless women, ongoing physiological and/or lifestyle imbalances are responsible for upsetting their inner clocks, including:

- hormonal imbalance

- certain dietary changes

- stress

- daily lifestyle habits

Circadian disturbance results in daytime fatigue and nighttime insomnia, often establishing an ongoing cycle that becomes hard to correct if not addressed quickly.

Do sleeping pills work?

The use of sleeping pills in America has more than doubled since 2000, and there are plenty of side effects to go along with the increase. People using Ambien have been found sleep-walking, bingeing on food, and even driving during the night with no memory of it the next morning.

Sleep aids are meant to treat temporary — not chronic — conditions. Most pharmacologic sleep aids, or hypnotics, are habit-forming. Sleeping pills may worsen chronic insomnia by further disturbing your natural sleep mechanisms.

Short-term use can help a chronic insomniac function, but sleeping pills won’t resolve the problem.

Instead, recent evidence shows that natural and behavioral approaches, like cognitive behavioral therapy and relaxation techniques, are more effective at treating long-term insomnia.

What is chronic insomnia and what causes it?

Waking up and staying alert during the night is a lonely and discouraging experience. But when it happens night after night, it can generate anxiety and a sense of desperation that can carry over into your daylight hours. Trouble sleeping every night for more than a few weeks is considered chronic insomnia, which can be broken down into two types: primary and secondary.

- Primary insomnia is a relatively short-term problem likely brought on by conditions that interfere with sleep, like worry and stress, uncomfortable sleep environment, alcohol consumption, smoking or drinking coffee too close to bedtime. Primary insomnia doesn’t seem to have significant physical or psychological causes at its root.

- Secondary insomnia is harder to trace because it occurs alongside, or as a result of, a medical or psychological problem that upsets sleeping patterns. It can be caused by medications, environmental factors, or physical issues such as perimenopause, hormonal imbalance, hot flashes, nocturnal leg or foot cramps, fibromyalgia, chronic pain, arthritis, breathing problems (sleep apnea, nasal polyps, nasal changes), insulin resistance, gastrointestinal disorders, mineral deficiencies, and urinary incontinence. Secondary insomnia can quickly become as bad as the condition that’s causing it. Finding effective relief is possible when you target both the primary health concern and the insomnia it’s causing.

How hormonal imbalance is connected to insomnia

Secondary insomnia can be one of the first signs of perimenopause, a time when many women wake up throughout the night — or are unable to fall asleep at all. Due to issues with temperature regulation and the fact that we’re getting older, perimenopause is a time when we typically spend less time in deep sleep. Both factors make you more sensitive to disturbances — even a minor increase in body temperature can wake you up. Another interfering factor is nighttime hot flashes, which are also usually accompanied by an adrenaline response, effectively putting your whole body on alert.

Temperature changes, hot flashes and night sweats can become maddeningly frequent during perimenopause and menopause, due to shifting hormones. Changing levels of estrogen may also be influencing both how much of the sleep hormone melatonin you produce and how your body responds to it. Impaired regulation of two major hormones, cortisol and/or insulin, are additional causes of nocturnal waking. Stress-related high cortisol disrupts normal sleep patterns.

The physical effects of insomnia

Feeling exhausted is an obvious consequence of insomnia, but inadequate sleep causes even worse problems because sleep is a restorative process for your body. When you’re asleep, your body detoxifies, repairs, builds muscle, and recharges your brain. During sleep your immune system is finally free to deal with any unfinished work from the day.

Lack of sleep upsets metabolism — studies link it to both obesity and type 2 diabetes. Long-term sleep loss can trigger or worsen insulin resistance, disrupt appetite, increase inflammation, and lead to a rise in the hunger hormone ghrelin and a restriction of leptin, the “I’m-full,” hormone. In one study, obese people got almost two hours less sleep than people with average body mass — so even a moderate increase in sleep may help heal your metabolism.

Chronic stress, poor diet, too much caffeine and insulin resistance all cause the adrenal glands to pump out extra cortisol. High cortisol levels keep us awake and alert, and also interfere with the production of DHEA, an important building block of sex hormones. Inadequate DHEA contributes to symptoms such as fatigue, reduced muscle mass, bone loss, aching joints, decreased sex drive, impaired immune function and depression.

Without the right amount of sleep, there is no way you can keep up with life’s demands, maintain stable moods, or balance your hormones, even if you think you’re doing okay on a few hours of sleep a night. Your body wants to sleep, and it will when it gets what it needs.

Find the source of your insomnia

What you do during the day has dramatic effects on your ability to sleep at night. Keep track of your sleeping conditions, also known as “sleep hygiene,” along with other factors that may be contributing to your insomnia:

- Foods you eat and when you eat them

- Caffeine, nicotine and alcohol consumption

- Medications, vitamins, minerals and supplements, and when you take them

- Stress and anxiety levels

- Exercise routines

- Menstrual cycle patterns

- Bedtime schedule

- Sleep environment, including temperature, light, noise, bed and bedding

Simply observing your behaviors and writing them down can reveal patterns that will then help you find out exactly what’s keeping you awake.

Get back to sleep — the Women’s Health Network approach

At Women’s Health Network, we believe you can resolve your insomnia naturally by creating the conditions for better sleep. Here’s what we recommend.

Tell your body it’s time to sleep at night

Establish a bedtime routine to send an internal message to your body and mind that it’s time to let go of the day and prepare for sleep. Experiment with some of these time-tested options: a relaxing bath before bedtime, meditation, reading, tidying up your bedroom, a cup of chamomile tea, aromatherapy (try lavender), and gentle stretching exercises or yoga.

Inventory your sleep hygiene

Set a firm bedtime, allotting an hour to wind down before you even try to go to sleep. Dim the lights, turn off the TV, cell phone and computer, and then make your bedroom as comfortable as possible. Choose calming colors and keep the room completely dark when it’s time to sleep, or wear a sleep mask. Block out any outside noise with earplugs. Keep your bedroom temperature on the cool side to help you stay asleep — 60-68 degrees is a good range. Key steps: eat your last meal at least four hours before bed, avoid caffeine after noon, and don’t have sugar, coffee, cigarettes and alcohol near bedtime.

Engage in physical activity during the day

Exercise helps relax your body and prepare it for sleep but don’t do it close to bedtime.

Empty your brain of disturbing thoughts

Jot down your current concerns on paper in the evening to help prevent anxious ruminations and circular thinking if you wake during the night.

Take a natural sleep aid

Try melatonin or a supplement with phosphatidylserine and/or L-theanine 45 minutes before bedtime. Many readers have success with our Sleep Reset Program that includes tips to help with your sleep hygiene.

Eat right for sleep

Focus on eating a balanced diet of whole foods. Make sure you also take a high-quality multivitamin/mineral supplement daily to help ensure adequate amounts of magnesium, calcium and folate. These can help with leg cramps and more.

Balance your hormones

Gently rebalance hormone levels, especially estrogen and progesterone, with herbal support. This can calm your nerves and help relieve other symptoms that might be interfering with your sleep. If your symptoms are so intense that they’re affecting your quality of life, see a healthcare practitioner.

Press the “pause” button — it’s time to rest

Insomnia is a highly treatable condition that doesn’t usually require sleeping pills. Quieting the conversation between your body and your mind as well as relieving hormonal fluctuations can improve your sleep patterns.

For more information on herbal sleep treatments, read our article Nature’s sleeping aids.

1 Wikipedia. 2009. Circadian rhythm. URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Circadian_rhythm (accessed 05.14.2009).

2 Cromie, W. 1999. Human biological clock set back an hour. Harvard University Gazette. URL: https://www.news.harvard.edu/gazette/1999/07.15/bioclock24.html (accessed 12.20.2006).

3 Morin, C., et al. 2009. The natural history of insomnia: A population–based 3-year longitudinal study. Arch. Int. Med., 169 (5), 447–453. URL (abstract): https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19273774 (accessed 05.15.2009).

4 Ancoli–Israel, S. 2006. The impact and prevalence of chronic insomnia and other sleep disturbances associated with chronic illness. Am. J. Managed Care, 12 (8), S221–S229. URL: https://www.ajmc.com/supplement/managed-care/2006/2006-05-vol12-n8Suppl/May06-2308pS221-S229 (accessed 05.15.2009).

5 Mayo Clinic. 2006. Insomnia: Causes. URL: https://www.mayoclinic.com/health/insomnia/DS00187/DSECTION=3 (accessed 12.28.2006).

6 Cagnacci, A., et al. 2000. Different circulatory response to melatonin in postmenopausal women without and with hormone replacement therapy. J. Pineal Res., 29 (3), 152–158. URL (abstract): https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11034112 (accessed 05.15.2009).

Okatani, Y., et al. 2000. Changes in nocturnal melatonin secretion in perimenopausal women: Correlation with endogenous estrogen concentrations. J. Pineal Res., 28 (2), 111–188. URL (abstract): https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10709973 (accessed 05.15.2009).

7 Datta, S., & MacLean, R. 2007. Neurobiological mechanisms for the regulation of mammalian sleep–wake behavior: Reinterpretation of historical evidence and inclusion of contemporary cellular and molecular evidence. Neurosci. Biobehav. Ref., 31 (5), 775–824. URL: https://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pubmed&pubmedid=17445891 (accessed 05.15.2009).

8 Spiegel, K., et al. 2005. Sleep loss: A novel risk factor for insulin resistance and Type 2 diabetes. J. Appl. Physiol., 99 (5), 2008-2019. URL: https://jap.physiology.org/cgi/content/full/99/5/2008 (accessed 05.15.2009).

Vorona, R., et al. 2005. Overweight and obese patients in a primary care population report less sleep than patients with a normal body mass index. Arch. Intern. Med., 165 (1), 25–30. URL: https://archinte.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/165/1/25 (accessed 05.15.2009).

References regarding use of sleep aids

a Saul, S. 2006. Record sales of sleeping pills are causing worries. New York Times. URL: https://www.nytimes.com/2006/02/07/business/07sleep.html (accessed 12.28.2006).

b Szabo, L. 2006. Insomnia drugs: A wake-up call? USA Today. URL: https://www.usatoday.com/news/health/2006-04-23-insomnia-drugs_x.htm (accessed 12.28.2006).

c Morgenthaler, T., et al. 2006. Practice parameters for the psychological and behavioral treatment of insomnia: An update. An American Academy of Sleep Medicine report. Sleep, 29 (11), 1415–1419. URL (abstract): https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17162987 (accessed 05.15.2009).